Museum

Museum  |

Bomber Command

|

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

|

Bomber Command

|

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

Museum

Museum  |

Bomber Command

|

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

|

Bomber Command

|

Aircrew Chronicles

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

Bomber Command Museum Chronicles

|

It was 4 o'clock, May 10, 1940 when we all woke up to the noise of German airplanes flying over and the noise of the Dutch army trying to shoot the planes down. The Germans bombed the airport "Waalhaven" at Rotterdam and captured it in no time. But the Dutch kept shooting and were quickly informed that they would bomb the city of Rotterdam if they kept shooting. So on the 14th of May they did bomb the heart out of Rotterdam. The Hauge would have been next, but by the 15th they called it off, after 5 days of fighting, we lost our freedom for 5 years. |

|

In 1941 the Germans started to arrest the Jews. Through the years it got worse. They were packed in trains to be taken to Germany to concentration camps where almost everyone lost their life. Two of my friends and I went by train to Leeuwarden which is in the very North of Holland. What we saw at the station was unbelievable. There were groups of Jews, tied to each other by ropes waiting for the right train to take them away. The S.S., "Social Security" was all over the place to watch if everybody behaved, and you better otherwise your life would be gone in a minute.

In the summer of 1942, I got a letter in the mail which ordered me to go to Rotterdam to get my papers to go to Germany. Everyone between the ages 18-46 was ordered to go to work for the Germans in the factories. But we knew by then that the English army went over every night in airplanes to bomb those factories. So there were two things a person could do, either work for the enemy or go underground, which meant to go somewhere to work in another town, which I decided to do. I got in contact with the "underground." They found me a place where I could work on a farm. I had to bring my bicycle and clothes etc. and somebody would bring me there. So at 10 o'clock in the morning I had to be at a certain place and there was policeman, who after four hours of biking dropped me off at a house where he left me after quick handshake with the owner, who brought me to the farm.

Without papers I couldn't go anywhere, so it was pretty lonesome. My parents didn't know where I was, so if someone came to look for me, they couldn't tell because they did not know. I knew later I had done the right thing because a cousin of mine the same age as I, did go to Germany and nobody had seen or heard from him ever after.

Now after about 6 months I wanted to go home, be home for Christmas, but how to do it was a problem. I thought maybe, if I asked the person who brought me here he might have an idea. But he didn't, it was too dangerous he said. I knew it, but I wanted to try, because I felt like it. I was nineteen at that time, but had never been away from home. Once in a while I went to the town, always only on a Sunday because on Sundays it was not too dangerous. So on this Sunday I went to the harbor, where the freight ships were loading with freight to bring to other towns on their route through the rivers and canals. Before I knew it I was talking to a couple of girls. I don't remember who spoke first, but it was good to talk to somebody. So I asked if they knew where those ships were heading. One of the girls said you want to go home don't you? I had seen her before at my boss's, place. Then one of those girls told me that her dad went to Rotterdam on Fridays. So I went to my contact man again. A week later I was on my way home. They gave me some old clothes and made me look about twenty years older. I had to keep the deck clean and was not allowed to talk to anybody. I had to act as a deaf person. We stopped at different towns to deliver freight, but finally ended up in Rotterdam. But on the wrong side of the river, I had to cross the river on a ferry. There was a big chance of being recognized, but everything went o.k. Then I had the choice to take the bus home or walk for about 12 km. I decided to walk. By then it was dark and there were no streetlights and no light shining through people's windows. We had to block out the lights so the planes going over at night wouldn't be able to see the towns and cities. So I made it home safe. I walked into the house and gave everyone a big scare. They wanted to know where I came from, where I had been and how I got home. I said, "I will tell when the war is over." From that time the whole Groeneveld family, set out to work for safety and rights.

The Hiding Place |

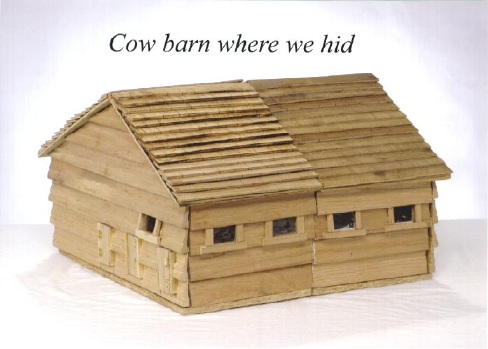

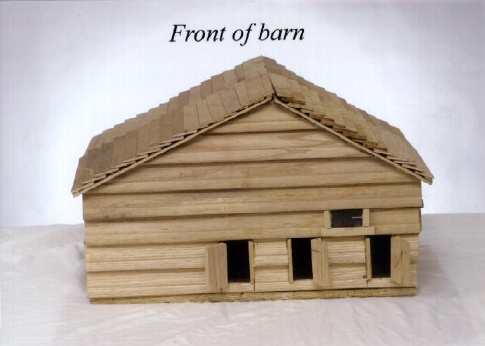

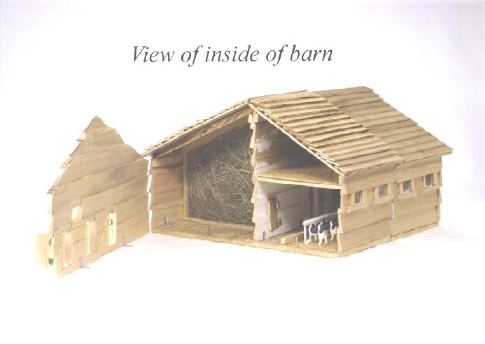

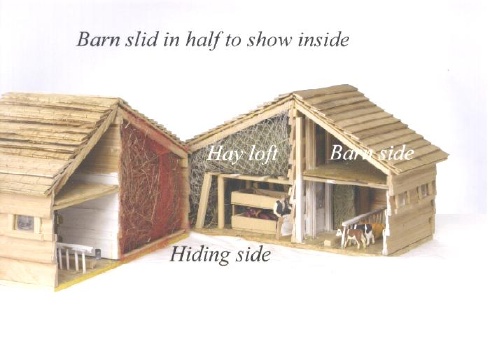

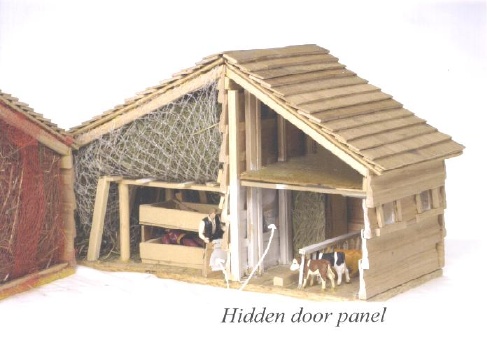

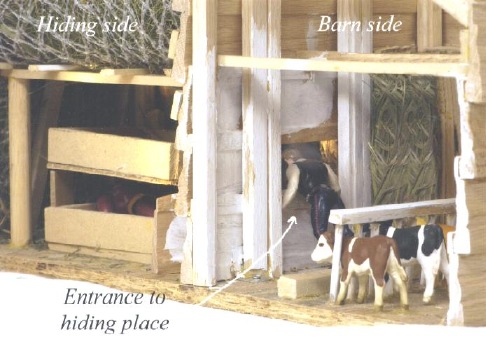

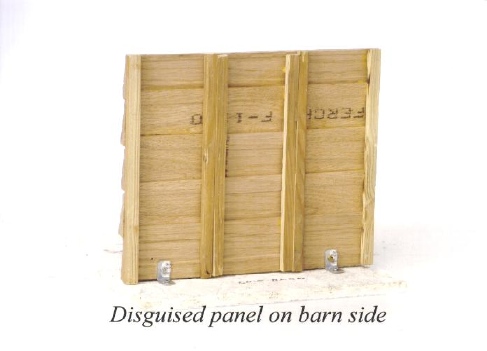

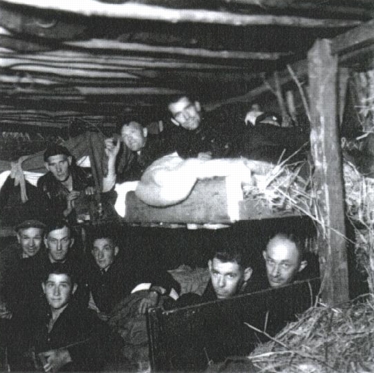

To begin with my Dad to told me that I couldn't sleep at home, so for about a month I slept wherever there was room for me. In the mean time, the enemy would block streets in the middle of the night and went from door to door to see if there were any men between 18-46. They took them right on the spot and transported them to Germany where they would be put to work in factories. The Germans set out to get 40,000 men in September of 1942 and another 35,000 in November of that year. It got more and more difficult to stay out of the Germans' hands. So I was thinking more and more about a way to stay out of their hands. I thought maybe, I could make a place in our barn. The barn had two rooms of equal size, one straw and hay and one for milking cows. In winter time the milk cows stay inside day and night, which made the barn quite warm. I decided to make a room in the middle of the hay, but the biggest part was to make an entry, which was invisible. We succeeded by making an opening to crawl through. Then there was the question about fresh air, would there be enough? We had to find that out after it was all done. My father had told me to make it big enough to have room for more people. It ended up being 10 feet by 9 feet, enough room for 5 people. There was a bunk bed and three single beds and if there were more people, then they slept on the floor. There were times when we had 10 people sleeping in that place. Usually people from "the underground" who were there because the Germans caught someone else. Worried about if they, the Germans, got that person talking; the other underground ones kept themselves scarce. |

|

I'll never forget the first night I slept in that place. So there we go, through the opening, lock it from the inside and there I stood, pitch dark all around me, I feel around to find the bed. Then the feeling of being safe make it all worth it. You will ask why we didn't use a flashlight? No batteries in the stores any more. By that time everything from hardware and clothing stores was taken to Germany. But to come back to my new bed, it was not as safe as I thought, because I saw two bright spots and heard some noise in the hay and on my bed. So I was in the company of some mice. They were my little friends for the rest of the time we spend in the hole. All we had for bathroom facilities was a pail, good thing we were still young, so we didn't have to use it to often. We made an agreement, to wait to get up when my father hit a steel pole with a hammer three times. So that was my first night. |

The Groeneveld's wartime home (the barn with the hiding place is just out of the photo to the right) |

The first few weeks were the worst. I felt so shut in and it was so dark and so quiet. But if you heard something that was no good either, because there was the thought of, what about if the S.S. is looking for me. And there were the thoughts of a fire, because the chances of getting out were pretty slim. After those first weeks, a friend of mine moved in with me. His name was Gerrit van Wijk. So then we could talk together.

Then soon after, the people from "the underground" came to ask my Dad if he wanted to take in somebody who was wanted by the Germans. When my father asked his name, they told him it was Wim Byl. If that is the guy who works for the Germans, my dad said then you better forget it. I'm not going to risk my life for him. But, why was "the underground" looking for a place for him? So they explained what was going on, and this is the story of Wim Byl. While he was working for the Germans, at the airport, he was able to collect a lot of information for the English. He did get caught, but escaped before, the S.S. looked for him, but couldn't find him. He was hiding in a cafe'. Someone warned him. He went upstairs and made it to the top of the roof. Luckily it was a flat roof, where he laid down till after dark. He couldn't go home, so that's why they came to our house. So after father heard the story, he agreed to keep him for a couple of weeks. Those weeks ended up being two and half years.

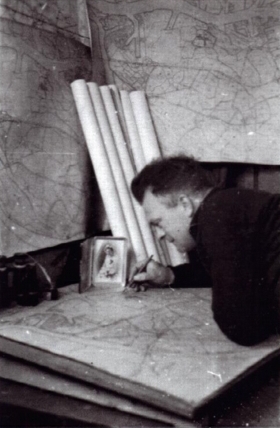

A while after he came to stay with us, the underground people came with information about where the Germans were fighting and what they were doing. Wim would take this information and make maps, which were sent to England through the underground. He also listened to radio England to know what was going on. People had to hide their radios because all radios were supposed to been turned in along with lots of other stuff. Anything made from gold, silver, steel, and copper had to be turned in to be melted to make more weapons.

In the mean time "the underground" had found out about our hiding place and asked if some of them could hide there too. And it did happen. More and more people were arrested and send to Germany, to be put to work in factories. Lots of them went "underground". The "underground" got stronger and stronger and did a lot of break-ins at office places where food stamps were stored. I.D. cards were also duplicated. They had to do this, because as soon as one went "underground" there were no more food stamps for them. Anyone, who was hiding someone, had to have those food stamps in order to feed an extra person.

Coming back to Wim Byl, he had heard through the grapevine, that Corrie, his wife, had given birth to their daughter. He wanted to go and see them, of course. So we put a horse in front of a wagon, a wooden crate on top of the wagon, Wim in the crate and went for a ride to see mom and baby. In the dark of evening he came back walking on his own two feet. Not until the end of the war did Corrie find out where Wim had stayed all those years.

|

The next excitement we had was, one morning, when my father came to give us the safety signal to get out. Usually he went in the house after that but this time he was still in the barn. When we came out of the barn the first thing I saw was a horse and wagon. The horse was tied up on the haystack and the wagon was full with wooden crates with a tarp over it. I walked up to it, but my father told me to stay away from it. But I wanted to know was what it was all about. But the answer was, "Don't ask so much, somebody brought it here, and I'm sure someone will get it back." So we went in to have breakfast, milked and fed the cows. Then at about 10 o'clock people started to come in the yard, some two together, some one by one. They started to unpack the wagon, brought all the boxes into the barn and opened them in front of our eyes. My eyes got bigger and bigger and I started to shake in my shoes. There were guns, handgrenades, stenguns, bazookas, brenguns and explosive material. There was enough for 25 - 30 men. This was all done under the Germans noses. It still makes me shake. No wonder, because those Germans were not very far away. Then every one started to clean those weapons, wiped all the grease and oil off, put them back in the crates and on the wagon. That was to give the impression that nothing stayed at our place. But that night two underground people came to put everything into our bedroom under hay and straw. That evening before going to bed, I stopped at the house for a few minutes. I heard my mother talking to my Dad. She said, "What are you doing Teunis? This is too dangerous. If we are found out by the Germans, all of us will lose our lives and many more, and they will burn this place down." Yes it was a big responsibility for my father, to take this all on his shoulders. I never knew for sure if he knew all about what was taking place, but I think he must have known. I do know that my mother had many sleepless nights after this happened. The stress was so great that she experienced many headaches and battled this the rest of her life. Going to bed that night was not easy, not only for what we went through, but also we lost half of our room. The next few days we spent our time pulling out some of the hay until we had enough room for the boxes. We bagged the pulled out hay in bags and fed it to the horses. |

Wym Byl and his maps |

Another thing I remember well is sitting in the kitchen with my father, listening to the planes flying over. This time they seemed to be flying back and forth. We were waiting for the bombs to explode, but nothing happened. Not long after, there was a knock at the door. We didn't have a hiding place at the house but I quickly went into a crawl space we had under the floor. Dad opened the door to a foreigner who stepped inside and closed the door behind him. We knew right away that he belonged to the Allies, because we couldn't understand him. We got in contact with one of "the underground" that spoke English. That's when we heard the story.

The English Soldier who turned himself in to the Germans |

Their airplane came back from a trip to Germany. They had been shot at and lost their instrument panel. Then they got low on fuel, so the pilot had told him to jump out, while he the pilot, would try to get to England. If he ever made it, we never heard, but most likely he drowned at sea because they thought they were above France. We asked the guy what he did with his parachute because if the Germans find something like that they wouldn't rest till they found out what it was all about. I went to look for it and luckily found it soon. I rolled it up and put it in a ditch, with some dirt over it. In the mean time, through the interpreter we told him what we were able to do for him, to get him back to England. But he was not interested, he figured as a POW "Prisoner of War" he would get fair treatment. We knew better, but he didn't believe us. So we left him on the street, to make believe, we had nothing to do with him. The police had him picked up in no time. About a month later, I went looking for the parachute again, found it and brought it home. Later my sister-in-law, a seamstress, made herself a wedding dress from the parachute, it turned out pretty good.  |

We are getting to the year 1944, when we were unable to buy anything without distribution stamps. The stamps we got were not enough to keep us alive. Especially in the big cities, people came to the countryside walking from door to door to get a little bit of food, a crust of bread or a piece of potato. If they were lucky to get a little more, they would take it home for their loved ones at home. But it got harder and harder for people who handed it out, after all there was only so much to go around. By now there were so many men, who had gone, "underground" who didn't get food stamps, but still had to eat too. There were also the Jews. The guns, which were stored at our place, were used to attack the distribution centers. I know of one place where 180,000 coupons were stolen, another one of 135,000. There were also thousands and thousands of coupons forged.

I remember well the time, when I had to bring guns etc. to a place on the end of the dike where we lived (about 2-3 km). The Germans had searchlights on that dike to search out the bombers who flew over on their way to Germany. Every time I went to milk the cows I had to pass thorough this restricted area. So this one-day I loaded those milk containers with guns put them on the wagon and pretended I was going to milk the cows. Since we passed that place quite often, we got to know some of the Germans there. This one man didn't even look at us, but always had a sugar lump for the horse and I had a chat with him. After that he would let us through, he must have been a farmer. Things were getting worse and worse. The only good in that was that we knew, it hardly couldn't get any worse, so there had to be an end soon. The Germans were losing everywhere and the bombers were flying over day and night. Sometimes on a clear day we would count them. Usually it was between 300 - 400 planes in an afternoon. The Germans saw the end coming too. They didn't get time to go on leave. They had to stay where they were, so they couldn't see what had happened at home, because most of the big cities were badly bombed. We were not allowed to talk together with three people or more on the street, so we quickly walked on.

Also the Germans dug big poles in big fields. Close enough together so no airplane could land in those fields. Well, try to do some plowing in a field like that. I pulled out many of those poles. That was not to wise after all, because when the fields were cleared later on, those poles were underneath the dirt. So plowing the next year was not much fun either.

The windmill where I hid |

It was about November 1944 that in Rotterdam and Schiedam 50,000 men were picked up for work in Germany. On the same time we had the Germans going through our farm, the house, the barn, every building on the property. Everyone except myself was able to get in our hole. I ran through the backdoor of the barn, through an orchard and soon there were bullets flying around me, I cried out and fell in the ditch. I fooled them, they believed they shot me. But I ran through the ditch, over the dike and on to the neighbor's house. The neighbors had a windmill and they allowed me to hide in the top of the windmill. At home every one was worried, nobody knew where I was. They saw the Germans poking with bayonets in the hay and straw of the barn. Luckily the barn was packed after harvest and the bayonets were not long enough to reach anyone. When they couldn't find anything they went looking for me but couldn't find me either. So they told my Dad they would set the place on fire if I had not showed up by evening. My neighbors had found out about this, but didn't tell me. Just told me to stay overnight, because it was still too dangerous to go home. Thank God the Germans DID NOT come back that night. So that all happened in 1944/45. |

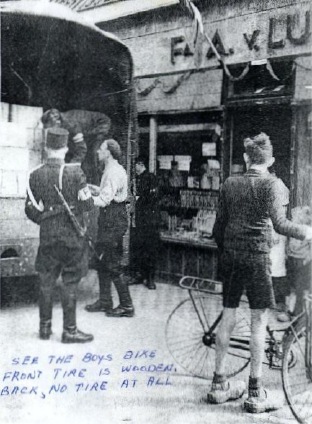

A real cold winter, there was no more coal to heat the houses, no oil for lamps, no gas for cars. Some people tried to fuel their cars with wood but that wasn't much of a success. Most people still had their bikes, but after the tires were worn out, that was the end of rubber tires. Although some people tried it on wooden tires, old rubber garden hose was another thing that was tried. Lots of houses had their wooden closet shelves and doors taken out, to be cut into pieces and burned in a homemade little stove to cook what little there was left to cook. At the same time they got a little heat. Trees were cut down and the posts the Germans had set in the fields saw their end in a heating stove. Until they were caught doing it. Then the older Dutch people were chartered to keep watch over these fields at night. It was just a laugh, for even when the older men did it; they would turn their heads when they saw someone stealing a pole.

Around this time the hunger in the big cities got so bad and some people were so skinny, we wondered if they would be able to get up if they fell. As a matter of fact there were lots of people who died right on the street where they fell. It was a very hard time for us, especially for my father. We knew people were eating tulip bulbs, but when people came asking for sugar beets. He said, "No way, no one should eat sugar beets, that's animal feed." He stood by his word for about two days, and then he broke down and said, "Just take them."

That they never shot my Dad, is still a wonder to me. He sold lots of milk for sick people for twenty-five cents a litre. Of course the Germans knew how much milk our cows should produce so when he was asked why there was so little milk, Dad always had an excuse. He would take his hat off, run his fingers through his hair and say he had slept in or that something went wrong, forever something else. They believed him. When they were gone, we laughed and he said, "Those people, you can tell them anything."

I remember one Saturday afternoon that father was helping people with milk. All of a sudden, there were two Germans who wanted some milk. They had two girls with them. Dad turned around and said, "You're not sick," and turned away. Dad felt a gun at his back, because the guy wanted milk. We stood, as if nailed to the ground What would happen now? Luckily the gun came down and the guys walked away without milk. There were lots of guardian angels around that day. What a relief that was.

Not too much later we heard that the guy, where we brought those guns in milk containers was shot to death. He was interrogated for about a week, what a scare, but he must have remained silent. Along with some more people from Rotterdam, he found his end. The "Underground" had tried to free him, but without success. The S.S. were getting meaner by the day.

That last winter, we were not able to get in or out of western Holland. They were trying to starve us all.

All but Western Holland was liberated in l944. It's real hard for me to write this all down and hard for anyone to understand what it is to live in fear so long and see so many people go hungry. We ourselves always had enough to eat also my wife, who I didn't know then. She has her own story, about an eight-year-old boy who came at the door about dinnertime. She gave him her plate of food. He said a thank you Lord prayer first. What faith for an eight-year-old boy and for her, she never forgot and never will. I will never forget the man who came to our door to ask for some food for his sick wife. My father just had to say no because they were running real low. The man took off his wedding ring and tried to trade it for some food. My dad got mad and said, "Put the ring back on." He would never do anything like that. The man was given a little bag of potatoes. Through radio England we heard that planes were loaded with food to drop over Western Holland. The Allies were negotiating with the Germans not to shoot at the planes. They kept their word. People were so happy, pretty soon the sky was full of planes, which were flying lower and lower in order not to damage their precious cargo as it was dropped. People were on top of buildings, on rooftops, on the street with flags and anything else to wave with. The planes came so low, that we could see the pilots and the rest of the crew. They made 5,356 mercy fights and dropped 10,913 tonne of food in 10 days. I wished then that I could talk to them and say "Thank you". |

Soon after the war was over, the stores were stocked with food again. This was a load of English biscuits. |

I came to Canada in April 1954 and in 1997 I got my wish. We visited the Nanton Lancaster Air Museum where we met somebody with the name of Joe English. He told how he had flown over Holland during the war to drop bombs over Germany. He said, The best dropping he ever did was when he dropped food to the starving people in Holland. So after 52 years I was able to shake hands and say Thank you. Also thank you to the rest of the crew and the crews of all the other planes.

If you or when you, read all this, you might wonder what happen to us. Are we are still thankful? Yes, we are. Thank you to all the Canadians who gave their lives so we could live and be free.

This all took place in Pernis, a town south of Rotterdam, Holland.

Ron had always wondered where the weapons that were brought to the Groeneveld family's farm came from and how they were delivered. Since writing his story, Ron has twice visited Holland to find out.

In 2004, I came in contact with the underground people in Berkel Roderijs. These people told me about the weapon droppings that took place around their town. There was a group of twenty people who were involved with these droppings.

In 2006 I returned to Holland and contacted the leader of the group, Jan Rozendaal. He told me that weapons were dropped eighteen different times. Spies also travelled with the weapons. Jan took me to a couple of places where droppings took place. One of these places was at a farm whose owner sold his vegetables to a market garden. The weapons were loaded onto wagons and covered with vegetables. The buyer took his purchase and had them loaded onto a small river boat. The weapons were hidden in the lower deck.

Now they were ready for the trip to our farm at Pernis, the most dangerous part of the journey. This small boat had to pass through all the canals of Rotterdam which were controlled by police and the SS. To get to the Maas River they had to pass through the locks which were also controlled and the SS would come aboard and check the boats. The Maas River was controlled by the SS in speed boats which on occasion would stop you and they would come aboard. But most times they would just wave as you passed by because this boat's skipper had a special permit to ship vegetables.

The weapons and vegetables arrived at the Pernis harbour for the farmers' market but were not unloaded because the skipper felt that there were spies observing the unloading. A secure spot had to be found for the unloading. After the bombing of Rotterdam all the rubble was hauled to the river's edge which provided a perfect hiding spot for unloading. The weapons were unloaded and placed in a horse-drawn wagon. For security reasons a driver would take the wagon to a town, tie up the horses and leave. A short time later another driver would come along and continue the journey. The driver tied up the horse at the Groeneveld farm and left.