Aircrew Chronicles

Aircrew Chronicles  |

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

Aircrew Chronicles

Aircrew Chronicles  |

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

|

Aircrew Losses

|

Nose Art

|

BCATP

|

Lancaster

|

Media

Bomber Command Aircrew Chronicles

Air Gunners

The statistics regarding those who served with Bomber Command are daunting. For every 100 aircrew, 60 were killed -a total of over 55,000. During the great offensives of 1943 and 1944, the short-term statistics foretold that fewer than 25 of each 100 crews would survive a tour of 30 operations. When a bomber went down over enemy territory, fewer than 20 percent of the aircrew survived. Of those who did not, some were killed by the flak, bullets, and cannon shells, others died in huge explosions when their bomber was hit, many were burned in their flaming aircraft, others fell to their deaths as the aircraft broke apart, and many were trapped by "G-forces" within the spinning, out of control bomber. Many aircrew who successfully escaped the aircraft drowned in icy waters and others were set upon and killed by infuriated civilians seeking revenge. Hundreds of pilots, rather than getting out themselves, controlled the doomed aircraft for as long as possible so that their crew might have a chance to successfully parachute from the plane. Al Hymers of Bruderheim, Alberta has been a regular visitor to the museum, attending almost all of our summer events. He was one of the lucky twenty percent who escaped from an aircraft that was going down. During the museum's "Salute to the Air Gunners" event in 2004, he described how he became the sole survivor of Lancaster LM-213.

|

|

My hometown is Winnipeg and that's where I joined the RCAF when I turned eighteen. At the time I joined they were not taking aircrew so I wound up ground crew and it took a few years before I finally got to re-muster. I tried out for a pilot but didn't make it. The war was getting on towards the end and I had to get into it so I volunteered to be a gunner. I went to Mont-Joli, Quebec where I took my gunnery training. We flew Fairey Battles with Bristol turrets. I went overseas and eventually wound up on an RAF squadron, No. 12, who were flying Lancasters which was fine with me. The Lancaster was the bird that everybody wanted to fly.

Our first trip was to Essen in the Ruhr Valley. That first trip -the flak and the searchlights and the bombs going down. It was absolutely beautiful -better than any fireworks display I've ever seen. As the trips progressed you began to realize that we were killing them and they're trying to kill you and the fear sets in. You don't really let that bother you because it's a short duration thing, eight to ten hours and you're back home. You go to the pub, get drunk, and have a good night's sleep in a bed with sheets. The food is fair and then away you go the next night to another hair-raising experience.

On my tenth trip we went to a German city called Zeitz -very deep into Germany. It was an oil refinery. We had a bad feeling about this trip -a premonition. We all had it. We discussed amongst ourselves whether we'd put the aircraft unserviceable. We decided, no, we'd go ahead and fly it. Who believes in premonitions? Anyway, we were over the target. We'd bombed and it was quite different there. There was a layer of thin cloud over the target and the fires below and the searchlights, there were hundreds of them playing on the cloud layer, made a glowing screen and every plane in the bomber stream was clearly visible from above. We knew there were fighters around because they were dropping fighter flares and the photoflashes were going off. It was quite spectacular.

Anyway, I had a nasty feeling we were being hunted. I was desperately looking around. I swung my turret around and looked down and there was the hunter, a Messerschmitt 410. He was tilted up about 25 yards away. I directed my guns down immediately and opened fire. At the same time I yelled for the skipper (F/O William Kerluk RCAF) to corkscrew. This all happened within a heartbeat. The fighter opened fire. I could see his four cannons blink once. One cannon shell took the two guns out of my turret on the left side. One hit under my feet and blew out the pipelines (the hydraulic lines that powered the turret) and the intercom. One hit the tail and one I'm sure went up the fuselage and killed the navigator. All this happened just like that. I opened fire. I yelled for the skipper to corkscrew starboard. All he heard was, "Corkscrew," before the cannon shell cut off the intercom. He's yelling, "Which way? Which Way?" I could hear him but he couldn't hear me. It was all over in seconds.

I opened fire when this happened and I could see my tracers bouncing off him. Then he broke away down and it was all quiet. I used the hand crank to turn my turret and my intercom came back on. So I told the skipper the enemy fighter was directly below us and we had about ten seconds to live. I told him to corkscrew or dive to the clouds or do something. The last words he said were, "I'm afraid to move it. The controls are shot up." I said, "Here he comes!" and he tilted up and opened fire. He hit us in the gas tanks and we started to burn. The flame was coming down the fuselage and out through my turret.

Luckily I was wearing the new seat pack -I was sitting on my parachute (Previously the rear gunner's parachute was stowed on a hook in the fuselage and the gunner had to reach behind into the fuselage and clip the parachute pack on). Now when you parachute out of a gun turret you unplug your intercom, your oxygen mask, your oxygen mask heater, and your heated suit. The flames were hitting me in the face. I tried to get my face out of the flames so that I could unplug. I leaned out the doors while I was doing this. The wind caught my parachute harness and I couldn't get back in to unplug anything. So I let go and everything pulled loose which was something of a miracle because they told you if you didn't unplug it usually breaks your neck.

Anyway there I am. It's about 15,000 feet at eleven o'clock at night and 50 below zero. I'm falling on my back. I could see the Lancaster going away. I could see the Messerschmitt 410 coming back. I reached for the ripcord with my right hand but I couldn't reach it because my Mae West had inflated. So I reached with my left hand and got my thumb in the D-ring, pulled it, and after a long pause the parachute opened. I looked down and there's my boots disappearing into the clouds. It seemed like a long, long time that I came down. As soon as I got below the clouds I realized that it was snowing quite heavily.

I couldn't see the ground but I kept looking down and all of a sudden there I was, "Bang." I landed in my stocking feet in a foot of snow. My Mae West had inflated so I couldn't reach the risers to deflate my chute and it was blowing me across the field. So I dug my hands in to think about what I was going to do next. I thought I'd get up and I'd run around the chute but the snow was too deep and in my stocking feet I couldn't do it.

So I was lying there and I saw a light coming. I knew I was in the middle of Germany so I thought, 'Well, I'll dig by hands into the snow and wait until this guy walks by and hope he doesn't see me in the falling snow.' He got behind me but a gust of wind blew me right into him and it turned out to be my wireless operator (F/S G.J. Harris). He was very badly burned. I grabbed him and I said hang on. I turned the quick release on my parachute. You bang it with your fist to release everything except that it was jammed. I kept banging it and banging it but it wouldn't open. So I got him to sit on my legs while I got my knife out and I cut away the parachute harness.

I looked at him. He was pretty bad. So I decided to give him a shot of morphine. I got my first aid kit out and I got the needle. I said, "Come on. I'll give you a shot of this and you'll feel a little easier." He'd have nothing to do with it. He was wild with pain and whatever. He was fighting me off. Finally I gave up and threw the thing away. He said, "There's a farm house over there. I'll give myself up and get some first aid." So I said, "Ok, I'll see you back in England." He disappeared into the snow. A while later I heard shots.

I knew I was in Germany but I didn't know where in Germany. I must have looked pretty damn conspicuous. I had cut off the legs of my electric suit and wound them around my feet. The sleeve of my electric suit had been burned off and so had my battle dress so everything was hanging by a thread here and a bunch of strings there. My face was burned so I got out the first aid kit. The first aid for burns was a dope called Gentian Violet. It was bright purple. So I got this purple ointment and smeared it on my face. I now had raggedy clothes and a purple face so I must have looked just a little suspicious.

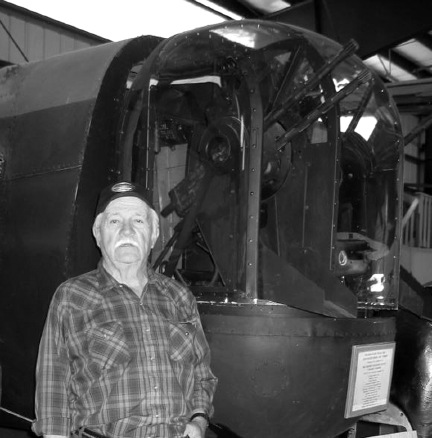

Al Hymers next to the Lancaster's rear gun turret in 2004. |

Al's escape from the doomed aircraft was just the beginning of his adventure. He evaded for several days, spending the daylight hours in haystacks, barns, and manure piles. At one point, while travelling cross-country at night, he stumbled across an anti-aircraft battery and found himself face-to-face with a sleeping sentry. Al was eventually captured. He was then subjected to mild forms of torture and his life was threatened during interrogation by the Gestapo. While travelling by train to a prison camp, he survived three attacks by Allied fighters. Together with thousands of other POW's, Al was marched for hundreds of miles as the war came to an end. During the march the prisoners were strafed and bombed by a group of fourteen American Thunderbolt fighter aircraft. Al recalled that he weighed 175 pounds when he was shot down and only 100 pounds when the war ended. Curious as to the fate of his wireless operator, Al inquired at the RAF casualty department in London after he returned to England. He was told that the Nazi's had reported that they, "found everybody else in the wreckage. I said, 'including the wireless operator?' 'Yes, including the wireless operator.' Now that's a lie. They murdered him." |