BCATP

BCATP  |

Lancaster

|

Media

|

Lancaster

|

Media

BCATP

BCATP  |

Lancaster

|

Media

|

Lancaster

|

Media

British Commonwealth Air Training Plan

|

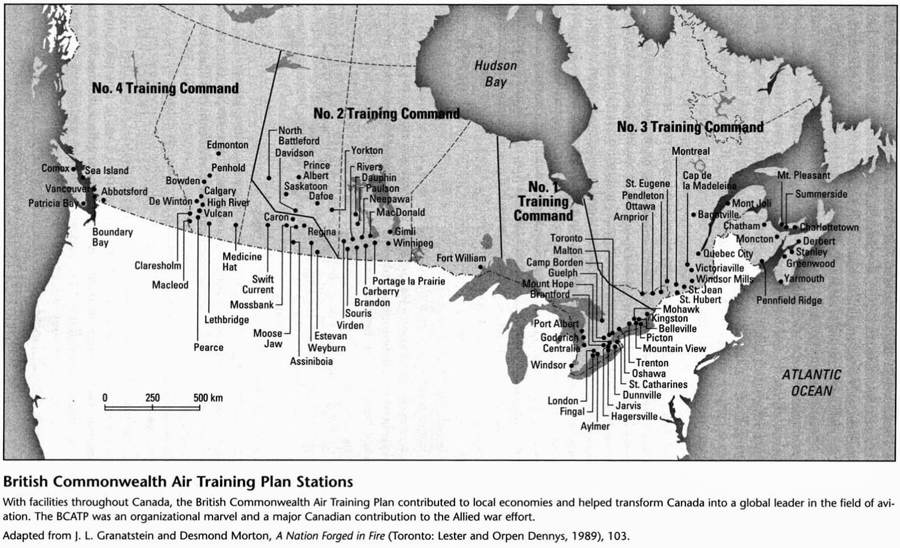

As the focus of a Commonwealth-wide effort to instruct aircrew, Canada made a major contribution to Allied air superiority during World War II. Called the "Aerodrome of Democracy" by US President Roosevelt, Canada had an abundance of air training space beyond the range of enemy aircraft,excellent climatic conditions for flying, immediate access to American industry, and relative proximity to the British Isles via the North Atlantic. Canada had been the location of a major recruitment and training organization during the First World War and Britain looked to it again when war began again in 1939. To Prime Minister King, the scheme had the advantages of keeping large numbers of Canadians at home and avoiding the raising of a large expeditionary force. Canada agreed to accept most of the plan's costs but insisted that the British agree that air training would take precedence over other aspects of the Canadian war effort. The British expected that their Royal Air Force would absorb Canadian air training graduates as in WW I, but King demanded that distinct Royal Canadian Air Force squadrons be formed. |

|

|

The construction of the training schools was a massive undertaking in itself. On the prairies, farmer's fields were transformed in a matter of a few months into operational schools. This involved the levelling and paving of runways, taxiways, and tarmacs: the building of several huge hangars, and dozens of other buildings for accommodating, teaching, and providing other services to the young airmen: and the installation of electrical, water, sewage, and other services. As well, an aircraft construction industry was developed to provide the thousands of aircraft necessary. As just one example of this , 1832 twin-engined Avro Anson Mk II's were built at factories in Nova Scotia and Ontario during the war. At the plan's peak, 94 schools operating at 231 sites across Canada, 10,840 aircraft were involved, and the ground organization numbered 104,113 men and women, and three thousand trainees graduated each month. At a cost of more than $ 1.6 billion, 131,553 pilots, navigators, bomb aimers, wireless operators, air gunners, and flight engineers were graduated. |

|

Recruits began their air force career with a four to eight week posting to a Manning Depot where they were issued with uniforms and learned the basics of military life such as marching drills, physical training, cleaning, and performing guard duty. If it was clear that a recruit was not suitable to be a pilot, they were then sent directly to train at bombing and gunnery, navigation, or wireless (radio) schools. Others who demonstrated a high level of mechanical ability were sent to St. Thomas where they learned aircraft maintenance skills. Pilot candidates were sent to Initial Training Schools. |

|

Following Manning Depot, prospective aircrew were posted to an Initial Training School for ten weeks. Ground school subjects such as mathematics, navigation, and aerodynamics were studied. There was no flying although students did spend some time in Link trainer simulators. Their results here determined their next posting, some being considered suitable for flying training and others were sent to bombing and gunnery, navigation or wireless schools. The courses were demanding and often required an academic background beyond the limits of high school graduates.

The first step for those who qualified for pilot training was a posting to an Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS). An eight week course involved all aspects of basic flight and navigation and about fifty hours of flying in the single engined "primary" training aircraft such as Fleet Finches, de Havilland Tiger Moths, and later in the war, Fairchild Cornells.

|

Successful graduates of an EFTS would be posted to a Service Flying Training School (SFTS) where students were expected to improve their navigational skills, master instrument and night flying, and participate in formation flying exercises. Most faced the challenge of adapting to flying larger, twin-engined aircraft such as the Avro Anson or Cessna Crane. Pilots who were judged to be suited to flying fighter aircraft flew the single-engined Harvard aircraft, much more powerful and demanding than the aircraft at EFTS. Upon graduation from an SFTS, the pilot was ready to continue his training at an Operationl Training Unit (OTU), generally in Britain. |

Other aircrew were assigned to BCATP schools devoted to their speciality such as navigation, wireless, and bombing and gunnery schools where a variety of aircraft were used in their training.

The presence of the BCATP base had a major effect on the nearby communities, not the least of which was providing a sizeable economic boost for towns which had still not recovered from the depression of the Thirties. The airforce personnel were generally made welcome and participated with the civilian population in various sporting, cultural, and social events both on the base and off. Inevitably romances developed and the concluding report of the BCATP reported that more than 3750 Canadian girls had married members of foreign forces who had been stationed in Canada.

With the massive presence in the Country of the BCATP, the RCAF was seen to be the service of choice for tens of thousands of young Canadians and of the total graduates of the Plan, 55% were Canadians with the others being primarily Britons, Australians, and New Zealanders. As the war progressed, this major commitment to the air war overseas, and particularly to Bomber Command, inevitably exacted a very heavy toll in Canadian casualties during operations.